The canine olfactory system represents one of nature’s most sophisticated biological detection tools, capable of interpreting chemical signatures at concentrations nearly 100 million times lower than what humans can perceive. At the heart of this extraordinary ability lies the olfactory mucosa—a specialized tissue lining the nasal cavity—packed with approximately 300 million scent receptors. To put this into perspective, humans possess a mere 5 to 6 million olfactory receptors. This staggering difference isn’t just quantitative; it reflects an evolutionary adaptation that has allowed dogs to navigate and interpret the world through an olfactory lens far beyond human comprehension.

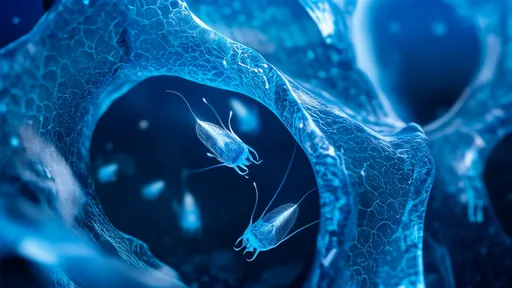

The architecture of the canine olfactory mucosa is a marvel of biological engineering. Unlike the relatively flat human olfactory epithelium, a dog’s nasal cavity contains a labyrinth of bony structures called turbinates, which increase surface area and create turbulence to maximize odorant capture. The mucosa itself is a mosaic of sensory neurons, sustentacular cells, and basal cells, all working in concert to detect, amplify, and transmit chemical signals. Each of those 300 million receptors isn’t a generalist but rather a specialist tuned to specific molecular configurations. This allows dogs to discriminate between subtly different compounds—like distinguishing the scent of ripe fruit from overripe or detecting a single drop of blood in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

What makes this system truly extraordinary is its integration with the canine brain. The olfactory bulb in dogs is proportionally 40 times larger than in humans relative to total brain size. This neural real estate processes scent information through a cascade of sophisticated pattern recognition, linking odors to memories, emotions, and even predictive scenarios. When a dog sniffs, it isn’t just identifying a smell—it’s constructing a multidimensional chemical map that includes temporal data (how old the scent is), directional information (where the scent is strongest), and emotional context (whether the source is fearful, excited, or ill). Recent studies using fMRI have shown that different odorants activate distinct neural pathways in the canine brain, suggesting a level of olfactory coding comparable to human visual processing.

The practical applications of this biological superpower are as diverse as they are revolutionary. Medical detection dogs can identify the volatile organic compounds associated with cancers, malaria, or even impending diabetic episodes with accuracy rates that rival clinical laboratory tests. In one documented case, a Labrador retriever consistently flagged a skin melanoma lesion that had been misdiagnosed by dermatologists. Similarly, conservation dogs track endangered species through fecal matter or fur samples across kilometers of dense terrain, while archaeological detection dogs can pinpoint human remains buried for centuries based on infinitesimal traces of decomposition byproducts.

Yet for all our scientific understanding, the subjective experience of a dog’s olfactory world remains tantalizingly elusive. Imagine walking into a café and perceiving not just the aroma of coffee, but the distinct scent profiles of each bean’s origin country, the fingerprint-like body odor of every patron, and the lingering traces of meals served weeks prior—all while detecting subtle hormonal shifts in nearby humans. This continuous stream of chemical data likely creates what researchers call an "olfactory panorama," a living, updating scent-scape that forms the primary framework for a dog’s perception of reality.

Technological attempts to replicate this system have yielded only partial successes. Electronic noses and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry can identify specific compounds but lack the canine system’s real-time processing, portability, and ability to learn through experience. Some research teams are experimenting with biosynthetic olfactory receptors or AI-driven sensor arrays that mimic neural processing, yet even the most advanced prototypes struggle with the "cocktail party problem"—isolating individual scents within complex mixtures, something dogs accomplish effortlessly.

The ethical implications of canine olfaction are only beginning to be explored. As we increasingly deploy dogs in medical, military, and forensic roles, questions arise about scent overload, informed consent (can a dog refuse to work certain scents?), and the psychological impact of constant exposure to traumatic odors like explosives or human remains. Some veterinary behaviorists advocate for "olfactory enrichment" programs that allow working dogs opportunities to engage in recreational sniffing—the equivalent of letting a bloodhound be a dog rather than just a biosensor.

Perhaps the most profound lesson from studying canine olfaction isn’t about scent at all, but about the limits of human perception. We evolved as visual creatures in a brightly lit world, while dogs developed as olfactory beings in a chemical soup we barely notice. Their 300 million receptors don’t just make them better smellers—they inhabit a parallel universe of information where time lingers in fading molecular trails, emotions broadcast as chemical signatures, and the invisible becomes tangible. In an era of environmental crises and emerging diseases, learning to "think like a dog" might hold keys to solving challenges our eyes alone cannot see.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025