The shimmering dance of goldfish in ornamental ponds has captivated human imagination for over a millennium. What began as a humble genetic mutation in Prussian carp (Carassius gibelio) during China's Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) blossomed into one of humanity's most enduring experiments in biological artistry. The journey from wild river dwellers to living sculptures with bubble-like eye sacs and flowing veiltails represents a fascinating intersection of cultural aesthetics, selective breeding, and biological plasticity.

Early records from the Jin Dynasty (265-420 AD) describe "red scaled fish" kept in imperial gardens, likely the first documented instance of intentional goldfish cultivation. Buddhist monks played an unexpected role in this story, maintaining ponds of golden-hued carp as symbols of mercy and protection against harm. These spiritual custodians unknowingly became the world's first goldfish breeders, isolating specimens with vibrant coloration from their silver-gray wild counterparts.

By the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD), goldfish husbandry had evolved from religious practice to aristocratic pursuit. Court documents describe specialized clay pots for rearing ornamental fish, marking the transition from pond cultivation to controlled container breeding. The genetic mutation causing the iconic xanthic (yellow-red) pigmentation became stabilized through generations of selection, producing fish we might recognize today as the common goldfish - though far removed from their modern descendants in fin shape and body proportions.

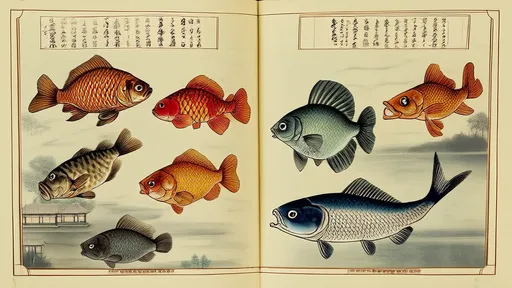

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) witnessed an explosion of morphological diversity as breeders began selecting for traits beyond coloration. Records from 1590 describe fish with "split tails like swallows' wings" and "protuberant eyes gazing heavenward" - early references to fantails and celestial eye varieties. This period saw the establishment of distinct breeding lines, with different regions specializing in particular traits. The imperial court maintained elaborate breeding programs, where eunuchs competed to produce ever more exotic forms to please the emperor.

Japanese cultivation beginning in the 16th century introduced new aesthetic sensibilities to goldfish development. While Chinese breeders favored symbolic traits (like the "dragon eye" representing imperial power), Japanese artisans pursued minimalist elegance. The development of the ranchu ("king of goldfish") in Osaka during the Edo period created a squat, rounded form lacking a dorsal fin - a radical departure from the streamlined ancestral shape. These cultural differences in breeding philosophy persist today, with Japanese varieties often displaying more restrained coloration than their Chinese counterparts.

European introduction of goldfish in the 17th century added another layer to this story. Initially reserved for nobility (the Duke of Richmond maintained goldfish ponds at Goodwood House in 1728), the fish became democratized through commercial breeding. Victorian era "fancy goldfish" shows drove selection toward extreme traits, with British breeders developing the bubble eye and lionhead varieties through intensive line breeding. This period also saw the first scientific studies of goldfish genetics, with Darwin referencing their variation in On the Origin of Species as evidence of selection's power.

Modern goldfish varieties demonstrate astonishing morphological specialization. The celestial eye goldfish, with upward-gazing pupils permanently fixed in a "stargazing" position, represents one extreme of selective breeding. These fish have such modified eye muscles that they cannot look downward, requiring special feeding techniques. Similarly, the bubble eye variety's fluid-filled sacs, while visually striking, make the fish exceptionally fragile. Such extreme traits raise ethical questions about animal welfare versus aesthetic pursuit - a debate that echoes concerns about purebred dogs and other domesticated species.

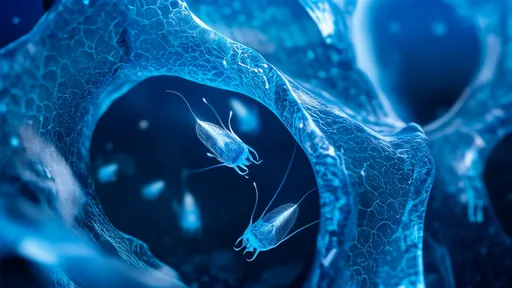

Contemporary genetic research reveals the molecular basis of goldfish diversity. The chordin gene, responsible for dorsal fin suppression in ranchu varieties, illustrates how single mutations can dramatically alter body plans. Pigmentation studies show that the classic "red-gold" color results from interactions between erythrophores (red pigment cells) and iridophores (light-reflecting cells), with over 40 genetic loci influencing color patterns. CRISPR technology now allows precise mapping of these traits, though traditional breeders continue relying on observational selection honed over centuries.

From Buddhist ponds to biotech labs, the goldfish's journey reflects humanity's complex relationship with domesticated species. These living artworks embody centuries of cultural values - from Chinese imperial grandeur to Japanese wabi-sabi aesthetics to Victorian eccentricity. As we admire their shimmering scales and whimsical forms, we witness not just biological diversity, but the evolving aspirations of human civilization itself, rendered in scales and fins.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025