In the shadowy underwater caves of the Dinaric Alps, a pale, serpentine creature defies one of nature's most fundamental rules. The olm, or Proteus anguinus, has astonished biologists by surviving without food for up to seven years – a record among vertebrates that challenges our understanding of metabolic endurance.

This blind amphibian, often called the "human fish" for its pinkish skin, moves through limestone caverns with glacial slowness. Its evolutionary strategy appears to be the antithesis of nature's typical "live fast, die young" approach. Researchers now believe the olm represents an extraordinary case of evolutionary energy optimization, having developed physiological mechanisms that make hibernation look like a brief nap.

The Metabolic Mystery

When Dr. Gergely Balázs first weighed marked specimens in a Bosnian cave system in 2010, he expected minor fluctuations. What he found instead was biological heresy. "We observed one female that lost just 0.002% of her body weight per day during 2,569 days of fasting," Balázs noted. "At that rate, she could theoretically survive a decade without eating."

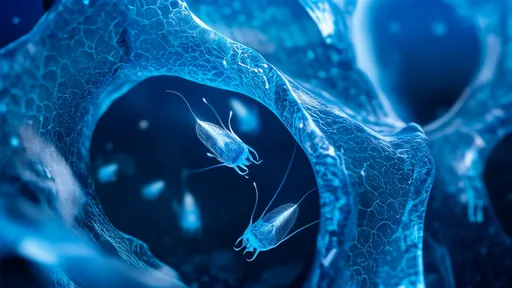

This metabolic near-standstill occurs without the olm entering true hibernation. Unlike bears that live off fat reserves, the cave-dweller appears to actively digest its own tissues in a controlled sequence – breaking down non-essential parts while preserving vital organs. Autophagy (cellular self-consumption) happens in all starving animals, but the olm's version resembles a meticulous librarian carefully removing single pages rather than burning entire books.

Survival Through Stillness

Every aspect of the olm's existence conspires to minimize energy expenditure. Its heart beats just eight to twelve times per minute – compared to 60-100 for humans – and it often remains motionless for years. Researchers have documented individuals occupying the same square meter of cave floor for over 28 months without discernible movement.

"They've turned passive existence into an art form," explains Dr. Kathrin Lampert, a comparative physiologist. "Their mitochondria operate differently, with electron transport chains that leak far fewer reactive oxygen species. This means they avoid cellular damage during long fasts that would kill other creatures."

This super-efficient metabolism comes with trade-offs. Olms take 14 years to reach sexual maturity and females reproduce just once every 12.5 years on average. When they do breed, the entire energy-saving system gets temporarily suspended. "We've seen feeding frenzies where they'll consume 20% of their body weight in shrimp, then return to fasting," says Lampert.

Climate Change Implications

The olm's abilities have captured the attention of NASA's extreme environment researchers. "Understanding how they protect muscle and neural tissue during prolonged starvation could revolutionize how we approach human space travel," notes astrobiologist Dr. Michael Meyer. Potential applications range from creating stasis protocols for Mars missions to improving organ preservation for transplants.

Conservationists warn that these ancient survivors now face unprecedented threats. Cave systems across Slovenia and Croatia are being altered by shifting rainfall patterns, with increased sediment affecting the olm's breeding caves. "A creature that evolved over millions of years to withstand starvation may not adapt quickly enough to rapid environmental change," warns Balázs.

As scientists continue decoding the olm's secrets, one truth becomes clear: in a world obsessed with productivity and growth, this cave salamander demonstrates the profound power of doing almost nothing at all. Its evolutionary strategy – perfected over 20 million years – suggests that sometimes, the ultimate survival technique isn't about finding more resources, but rather mastering the art of needing less.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025