The ancient Chinese art of silkworm domestication stands as one of humanity's earliest and most remarkable feats of biological engineering. For over five millennia, Chinese sericulturists have perfected the delicate dance of coaxing Bombyx mori moths into producing the world's finest natural fiber. This extraordinary legacy, often called the "Silkworm Code," represents not merely an industrial process but a profound cultural symbiosis between humans and insects.

Recent archaeological discoveries along the Yellow River basin have pushed back the timeline of sericulture to approximately 3600 BCE. Excavations at Neolithic sites reveal primitive spinning tools and carbonized silk fragments that predate the legendary accounts of Empress Leizu's accidental discovery. What began as wild silk harvesting from forest-dwelling moths evolved into a sophisticated indoor rearing system that completely transformed the insect's biology and behavior.

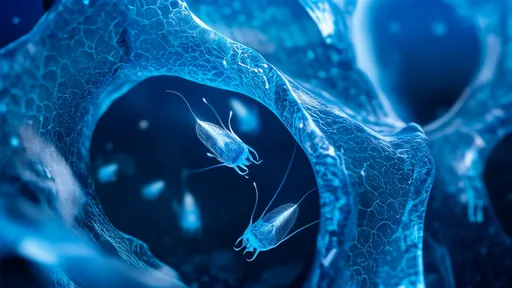

The domesticated silkworm moth we know today bears little resemblance to its wild ancestors. Centuries of selective breeding have rendered Bombyx mori flightless, visually impaired, and entirely dependent on human care. Their cocoons produce nearly a kilometer of continuous filament - ten times longer than wild varieties. This biological manipulation occurred through meticulous observation and undocumented trial-and-error that modern scientists still struggle to fully decode.

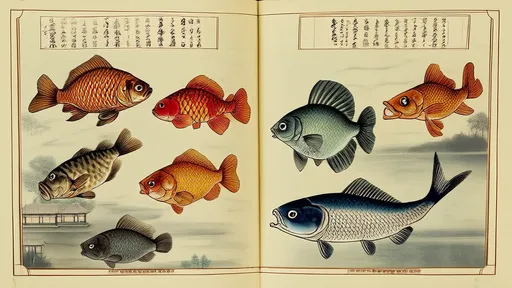

Traditional Chinese rearing manuals contain cryptic references to environmental triggers that modern entomology is only beginning to understand. The "three silences and seven precautions" method describes specific sound frequencies that affect cocoon spinning. Ancient practitioners used particular types of mulberry leaves at precise lunar phases to enhance silk quality - techniques that contemporary research has shown to influence the expression of fibroin proteins.

Perhaps most astonishing is the historical control over silkworm diapause - the insect's hibernation-like state. By regulating temperature and humidity in specially designed rearing chambers, Chinese sericulturists could induce multiple generations per year. This breakthrough, achieved centuries before Gregor Mendel's pea experiments, allowed for continuous silk production rather than being limited to seasonal harvests.

The cultural transmission of sericulture knowledge followed unique pathways. For generations, the craft remained a closely guarded secret among women in imperial households. Specialized silkworm palaces within the Forbidden City housed both the insects and their caretakers under strict isolation. Technical knowledge was often encoded in poetry or visual art rather than written manuals, creating layers of metaphorical meaning that modern researchers must decipher.

Contemporary applications of this ancient wisdom are emerging in surprising fields. Biomedical engineers study silkworm cocoon architecture for tissue scaffolding designs. Materials scientists replicate the natural spinning process to create artificial spider silk. Even computer programmers have drawn inspiration from the binary-like patterns found in traditional silkworm rearing charts for data encryption algorithms.

As genetic sequencing reveals more about the epigenetic modifications in domesticated silkworms, we gain deeper appreciation for this Neolithic biotechnology. The Silkworm Code represents more than just textile production - it's a testament to humanity's ability to shape evolution through sustained cultural practice. In an era of synthetic materials and genetic engineering, these ancient techniques continue to offer profound insights into sustainable biological manufacturing.

Preservation efforts now face urgent challenges. Climate change threatens mulberry cultivation patterns maintained for centuries. Younger generations show decreasing interest in mastering the intricate timing and tactile skills required for traditional sericulture. UNESCO's recognition of Chinese silkworm rearing as intangible cultural heritage has spurred documentation projects, but much knowledge remains vulnerable as elder practitioners pass away.

The legacy of Chinese silkworm domestication endures in unexpected ways. From the silk proteins used in surgical sutures to the biomimetic materials inspired by cocoon structures, this ancient technology continues to shape our modern world. As scientists decode the molecular secrets behind centuries of empirical breeding, the full scope of this Neolithic biotechnology revolution is only now coming into focus.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025