The centuries-old tradition of Teochew fish sauce fermentation represents one of humanity's most ingenious food preservation techniques, harnessing the power of salt gradients and osmotic pressure to transform humble marine ingredients into complex umami-rich condiments. This biochemical alchemy, perfected through generations of Chaozhou artisans along China's southeastern coast, operates on principles that modern science is only beginning to fully comprehend. At the heart of this process lies an elegant dance between microbial ecology and physical chemistry, where controlled decomposition meets precise mineral balance.

The Living Amphora: Unlike industrialized fish sauce production that relies on forced fermentation, traditional Teochew methods employ massive earthenware jars that breathe like living organisms. These porous vessels, some taller than a grown man, create micro-environments where salt concentration decreases gradually from top to bottom. This vertical salinity gradient - often ranging from 25% brine at the surface to nearly freshwater conditions near the base - establishes what microbiologists now recognize as a "trophic cascade" of enzymatic activity. Halophilic archaea dominate the upper layers, while proteolytic bacteria thrive in middle zones, and bottom-dwelling yeasts complete the flavor profile.

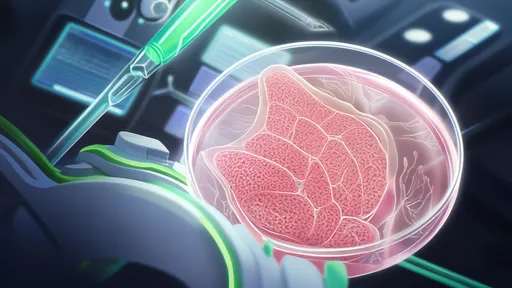

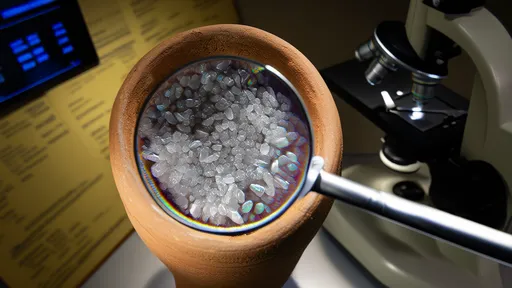

Osmotic Archeology: Recent studies of 19th-century fermentation pits in Shantou reveal how Teochew masters empirically developed what we now term "selective permeability management." By layering fish (typically anchovies or sand lance) with alternating strata of sea salt and rock salt, they created differential osmotic pressures that methodically break down proteins into peptides and free amino acids. The heavier mineral crystals sink slowly, establishing convection currents that redistribute enzymes while preventing putrefaction. This self-regulating system maintains a dynamic equilibrium where water activity (aW) never drops below 0.85 - the critical threshold for pathogenic microbe suppression.

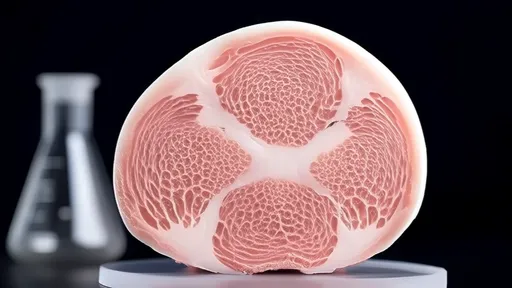

The biochemical ballet within these jars follows a precise choreography. During the initial "salt shock" phase lasting 40-60 days, high surface salinity (reaching 30% NaCl) induces plasmolysis in fish cells, rupturing membranes to release cathepsin enzymes. Meanwhile, the gradient's lower layers (15-18% salinity) foster Lactobacillus colonies that acidify the environment to pH 5.2-5.8. This Goldilocks zone allows autolysis while inhibiting histamine formation. Artisans monitor the process through generations-honed indicators - the viscosity of drippings, the iridescence of surface films, even the sound of bubbles rising through the column.

Molecular Migration: Advanced isotopic tracing demonstrates how amino acids undergo selective transport across the salinity gradient. Glutamic acid and aspartic acid (key umami compounds) concentrate at mid-levels where 18-20% salinity optimizes enzymatic conversion. Meanwhile, bitter-tasting leucine and valine either degrade or settle toward the base. This natural chromatography effect explains why traditionally fermented Teochew fish sauce achieves flavor complexity unattainable through uniform brining. The gradient also facilitates stepwise lipid hydrolysis - surface lipases generate short-chain fatty acids that gradually esterify into fruity aromas as they descend.

The temperature moderation inherent to underground fermentation pits (maintaining 22-28°C year-round) allows this process to unfold over 12-18 months. Modern attempts to accelerate production through uniform salination and heated tanks invariably produce harsh, one-dimensional flavors. Teochew masters compare this to the difference between a pressure-cooked stew and one simmered for days - the gradient method allows flavors to develop symphonic harmony rather than chaotic noise.

Microbial Terroir: DNA analysis of century-old starter cultures reveals unique regional microbiota including Salinivibrio costicola and Tetragenococcus halophilus strains found nowhere else. These extremophiles have co-evolved with Teochew fermentation practices, producing enzymes like salt-activated protease SCP-1 that cleave proteins at distinct sites compared to commercial enzymes. The porous ceramic vessels themselves host biofilms that contribute to flavor; X-ray fluorescence shows zinc and magnesium leaching from the clay catalyze Maillard reactions during the final maturation phase.

Contemporary food scientists are now adapting these principles for novel applications. Gradient fermentation has inspired everything from accelerated koji production to specialty cheese aging. Some molecular gastronomy chefs have even created "reverse fish sauce" by inverting the salinity gradient to produce entirely different flavor profiles. Yet none can quite replicate the depth of traditional Teochew fish sauce - a testament to how ancestral wisdom often anticipates modern biochemistry.

The sustainability aspects of this ancient method are equally remarkable. By utilizing the self-sorting properties of salt gradients, the process requires no energy input beyond sunlight for evaporation. The ceramic jars last generations, and the technique accommodates seasonal variations in fish supply. Modern life cycle assessments show traditional fish sauce fermentation has a carbon footprint 93% lower than industrial equivalents - making it both a culinary treasure and a model for circular food systems.

As climate change alters marine ecosystems, preserving this knowledge becomes crucial. Rising ocean temperatures already affect the lipid composition of anchovies, requiring subtle adjustments to salt ratios. Teochew masters speak of "listening to the jar" - interpreting subtle changes in fermentation sounds and odors to maintain quality. This sensory expertise, combined with emerging scientific understanding of gradient dynamics, may hold answers for developing resilient fermentation technologies in our changing world.

From Michelin-starred kitchens to food science laboratories, the Teochew salt gradient method is gaining recognition as a masterpiece of biochemical engineering. Its layered approach to controlling microbial succession through osmotic pressure offers lessons far beyond fish sauce - perhaps even clues to pre-industrial waste treatment or pharmaceutical production. As we peel back the layers of this ancient practice, we find increasing evidence that our ancestors understood the rhythm of molecules long before we had the tools to observe them.

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025