The discovery of the Iceman, affectionately known as Ötzi, in the Ötztal Alps in 1991 was a watershed moment for archaeology. Among the many revelations his remarkably preserved body offered, perhaps none is as intriguing as the contents of his stomach. The last meal of this Copper Age man, consumed over 5,300 years ago, provides a fascinating glimpse into the diet, lifestyle, and even the environmental conditions of his time. Scientists have meticulously analyzed the stomach contents, revealing a menu that is both surprising and telling. This "Alpine stomach contents recipe" not only sheds light on Ötzi’s final hours but also opens a window into the culinary habits of our ancient ancestors.

The Last Supper of the Iceman

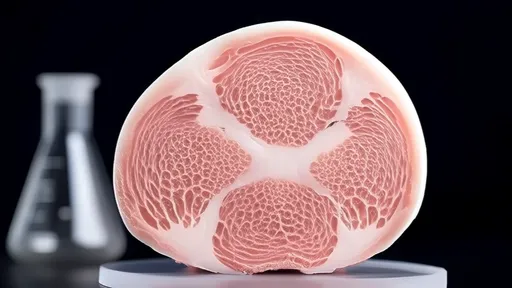

Ötzi’s stomach contained a mixture of wild game, cereals, and traces of toxic fern, painting a picture of a meal that was both hearty and, perhaps unintentionally, hazardous. The primary component was ibex meat, a type of wild goat that still roams the Alps today. This suggests that Ötzi was either a skilled hunter or part of a community that relied heavily on hunting for sustenance. The meat was likely dried or cooked, as the high-fat content would have provided much-needed energy for the harsh alpine environment. Alongside the ibex, researchers found traces of red deer, another staple of the prehistoric Alpine diet. The presence of both animals indicates a diverse intake of protein, essential for survival in such a demanding landscape.

The meal wasn’t purely carnivorous, however. Ötzi’s stomach also contained remnants of einkorn wheat, an ancient grain that was one of the first crops domesticated by humans. This suggests that Ötzi’s diet was balanced, incorporating both hunted and farmed foods. The einkorn was likely consumed as a type of bread or porridge, a carbohydrate-rich complement to the protein-heavy meat. Interestingly, the wheat was not finely ground, indicating that the processing techniques of the time were rudimentary. This coarse texture would have made the bread dense and chewy, a far cry from the fluffy loaves we enjoy today.

A Toxic Addition

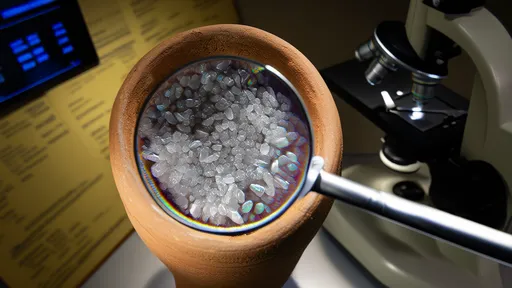

One of the most puzzling discoveries was the presence of bracken fern spores in Ötzi’s stomach. Bracken fern is known to be carcinogenic and toxic to humans, raising questions about why it was included in his last meal. One theory posits that the fern was used as a wrapping for the food, much like banana leaves are used in some cultures today. Another possibility is that Ötzi consumed it for medicinal purposes, as some ancient cultures believed ferns had healing properties. A darker interpretation suggests that the fern was ingested accidentally, perhaps as a last resort during a period of starvation or desperation. Whatever the reason, its presence adds a layer of mystery to Ötzi’s final hours.

The Environmental Clues

Beyond the dietary insights, Ötzi’s stomach contents offer valuable information about the environment in which he lived. The ibex and red deer meat indicates that these animals were abundant in the region, suggesting a thriving ecosystem. The einkorn wheat, on the other hand, points to the early stages of agriculture in the Alps. This combination of hunting and farming highlights a transitional period in human history, where communities were beginning to settle but still relied heavily on wild resources. The bracken fern, commonly found in wooded areas, further suggests that Ötzi’s last meal was prepared in or near a forested region, possibly close to where his body was eventually discovered.

The stomach contents also reveal the time of year Ötzi died. The presence of certain pollen grains indicates that his last meal was consumed in the late spring or early summer. This aligns with other evidence, such as the clothing he was wearing and the tools he carried, which suggest he was prepared for a journey through high-altitude terrain. The seasonal timing adds another piece to the puzzle, helping researchers reconstruct not just what Ötzi ate, but also the circumstances surrounding his death.

A Window into Copper Age Cuisine

Ötzi’s last meal is more than just a curiosity—it’s a snapshot of Copper Age cuisine. The combination of wild game, ancient grains, and foraged plants reflects a diet that was both practical and adaptable. It’s a diet shaped by necessity, tailored to the demands of a life spent in one of Europe’s most challenging environments. The ibex and red deer provided the protein and fat needed to sustain physical exertion, while the einkorn wheat offered a reliable source of carbohydrates. The bracken fern, whether intentional or not, underscores the trial-and-error nature of ancient food practices.

What’s striking is how little some aspects of our diet have changed. The basic components of Ötzi’s meal—meat, grains, and greens—are still staples in many modern diets. The methods of preparation may have evolved, but the fundamental principles of nutrition remain the same. This continuity speaks to the ingenuity of our ancestors, who, without the benefit of modern science, managed to craft diets that were both sustainable and nourishing.

Conclusion: A Meal Frozen in Time

Ötzi’s stomach contents are a time capsule, preserving a moment in history that would otherwise be lost to the ages. They tell a story of survival, of a man who relied on the resources around him to fuel his journey through the Alps. They also remind us of the deep connection between diet and environment, a relationship that continues to shape our lives today. The "Alpine stomach contents recipe" is more than a list of ingredients—it’s a testament to the resilience and adaptability of humanity. As we continue to study Ötzi and his world, we gain not just knowledge of the past, but insights that could inform our future.

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025