Deep within the labyrinthine passages of Egypt's pyramids, archaeologists have uncovered a substance so enduring it defies the very concept of time. Amidst golden sarcophagi and hieroglyphic inscriptions, clay pots filled with honey – still edible after three millennia – stand as silent witnesses to humanity's oldest love affair with sweetness. These ancient jars, discovered in pharaonic burial chambers, contain honey that retains not only its physical form but remarkably, its flavor and nutritional properties.

The discovery of 3000-year-old honey in Tutankhamun's tomb sent shockwaves through the scientific community. When British archaeologist Howard Carter broke the seal on a small amphora in 1922, he expected dust. Instead, he found viscous, golden liquid – honey so well preserved it might have been harvested yesterday. This wasn't merely a lucky preservation fluke; multiple tombs have yielded similar finds, suggesting the ancient Egyptians mastered honey preservation as part of their death rituals.

Why honey? The answer lies in the sacred significance bees held in Egyptian cosmology. Hieroglyphs depict bees as tears of the sun god Ra, falling to earth and transforming into insects. Temple walls show elaborate honey harvesting scenes, while medical papyri prescribe honey for everything from wound treatment to fertility enhancement. For a civilization obsessed with eternity, honey's resistance to spoilage made it the perfect symbol of immortality – a food that, like the soul, never dies.

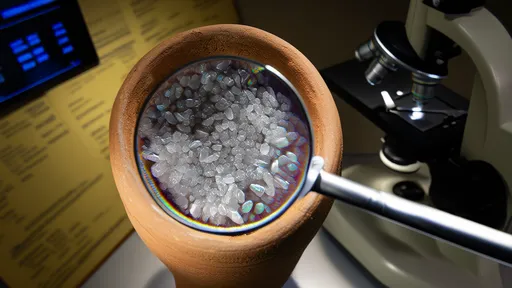

The chemistry behind honey's eternal shelf life reads like an ancient alchemical formula. Its low water content and acidic pH create an environment where bacteria and microorganisms simply cannot survive. Egyptian honey takes this a step further – the clay storage vessels were sealed with linen and resin, creating an anaerobic environment that halted oxidation. Modern scientists testing these ancient samples found them microbiologically sterile, with pollen profiles revealing precise geographic origins of the nectar sources.

Beyond its symbolic value, honey played practical roles in mummification. Recent spectroscopic analysis of mummy wrappings has detected honey residues mixed with plant resins. The antibacterial properties likely aided preservation while the sticky consistency helped bind layers of linen. Some Egyptologists now believe the famous "mummy's curse" may originate from toxic spores that developed in improperly sealed honey containers within tombs – a deadly legacy of the pharaohs' sweet tooth.

Contemporary beekeepers along the Nile still use traditional methods strikingly similar to those depicted in ancient reliefs. Cylindrical hives made of Nile mud, smoke to calm the bees, and careful harvesting techniques have changed little since the time of Cleopatra. The wildflower varieties that bloom along the river's floodplains – including the same lotus and clover species found in ancient honey samples – continue to produce honey with distinctive flavor profiles that modern gourmets prize.

In museum conservation labs, researchers employ lessons from these ancient honey preservation techniques. The Getty Conservation Institute has adapted Egyptian clay vessel designs for storing delicate organic artifacts, while pharmaceutical companies study ancient honey's antibacterial compounds. Perhaps most remarkably, geneticists are sequencing DNA from ancient honey samples to reconstruct Bronze Age ecosystems – making the pharaohs' golden treasure a time capsule of biodiversity.

The next time you drizzle honey into tea or spread it on toast, consider that you're consuming the only food that never spoils, a substance so stable it outlasted entire civilizations. Those clay pots in the Valley of the Kings hold more than just honey – they contain humanity's enduring longing for sweetness, both literal and metaphorical, and proof that some things truly can achieve immortality.

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025