The vast deserts, with their relentless winds and scorching sun, have long been a crucible for unique culinary traditions. Among these, the practice of drying camel meat through natural wind erosion stands as a testament to human ingenuity in harsh environments. This ancient method, known as "desert dry-aging," transforms raw camel meat into a preserved delicacy through a combination of atmospheric conditions and time. The resulting product—chewy, intensely flavored, and rich in nutrients—has sustained nomadic cultures for centuries and now garners interest from gourmets and food scientists alike.

The Science Behind Wind-Driven Dehydration

At the heart of this process lies a delicate interplay between environmental factors and biochemical changes. Unlike industrial dehydration, which relies on controlled heat, desert dry-aging employs the persistent low-humidity winds that sweep across arid regions. These winds act as a natural desiccant, gradually extracting moisture while allowing enzymatic breakdown to tenderize the meat. The phenomenon can be partially explained through adaptations of the Ollier-Wind Erosion Model, typically used in geological studies but proving remarkably applicable to this culinary context.

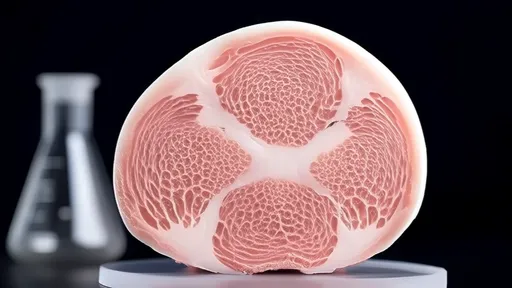

Researchers have observed that the meat's surface develops a hardened crust within 72 hours of exposure, creating a protective barrier against microbial contamination while permitting controlled internal moisture migration. This outer layer, resembling a leathery membrane, forms through a combination of protein denaturation and lipid oxidation—processes accelerated by the desert's ultraviolet radiation. Meanwhile, the meat's interior undergoes what food anthropologist Dr. Elias Marrouf describes as "a slow-motion fermentation," where naturally occurring enzymes break down connective tissues without putrefaction.

Cultural Roots and Modern Rediscovery

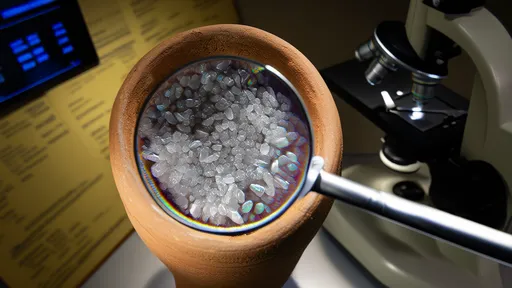

Historical records from Saharan trade routes indicate that Tuareg caravans perfected this technique over millennia, slicing camel hump meat into thin strips and suspending them from wooden frames during seasonal wind patterns. The Bedouins of Arabia developed their own variant, incorporating brief saltwater brining before exposure to coastal desert winds. These regional variations produced distinct textures—the Saharan method yielding a brittle, almost translucent product, while Arabian versions maintained a pliable chewiness.

Contemporary chefs have begun experimenting with controlled replicas of this process, installing wind tunnels that simulate desert conditions in urban kitchens. Notable among these is Dubai-based restaurateur Yasmin al-Rashid, whose "Darb al-Badawi" pop-up serves wind-aged camel carpaccio paired with fermented palm sap. "We're not just preserving meat," she explains, "we're preserving a dialogue between landscape and sustenance." Meanwhile, food engineers in Mongolia have developed mathematical models predicting optimal dehydration rates based on wind velocity, meat thickness, and solar azimuth angles.

Nutritional and Economic Implications

Recent nutritional analyses reveal surprising benefits from this unconventional preservation method. The extended exposure to sunlight triggers vitamin D synthesis within the meat, while wind-driven dehydration concentrates iron and zinc content by up to 40% compared to fresh cuts. These findings have sparked interest among humanitarian organizations exploring the technique's potential for creating shelf-stable protein sources in arid developing regions.

On commercial fronts, boutique producers are capitalizing on the method's artisanal appeal. A single kilogram of properly wind-aged camel loin now commands prices exceeding $300 in Tokyo's luxury food markets, where connoisseurs prize the distinctive umami flavor derived from months of gradual dehydration. However, traditional practitioners warn against commodification—as Mauritanian elder Sidi ould Mohammed cautions, "The desert gives flavor only to those who understand its rhythm."

The phenomenon even shows potential applications beyond gastronomy. Biomedical researchers at the University of Nouakchott have published preliminary studies on antimicrobial compounds extracted from the meat's protective crust, possibly leading to new food preservation technologies. Meanwhile, climate scientists monitor how shifting wind patterns due to desertification may alter traditional drying practices, creating an unexpected intersection between culinary heritage and environmental monitoring.

As global culinary boundaries continue to blur, the ancient art of wind-eroded camel dehydration stands as a remarkable example of how extreme environments shape human innovation. From nomadic survival tactic to haute cuisine darling, this practice embodies the persistent human quest to transform adversity into artistry—one sun-blasted, wind-whipped strip of meat at a time.

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025