In a groundbreaking discovery that sheds light on the culinary practices of our Neolithic ancestors, researchers have identified traces of what appears to be the world's oldest known porridge. The finding comes from meticulous analysis of starch grains preserved in the crevices of ancient pottery fragments, specifically from a type of cooking vessel known as a Tao Li - a distinctive tripod pottery used extensively during China's Neolithic period.

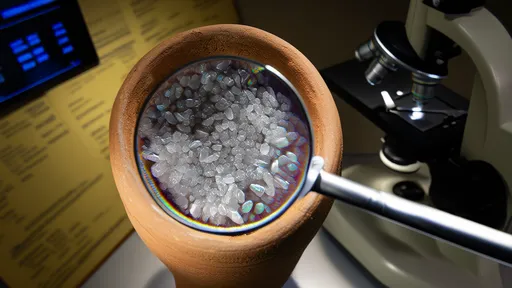

The archaeological team, led by Dr. Liang Wei from the Institute of Archaeological Science at Peking University, employed advanced microscopic techniques to examine residues found in pottery shards excavated from several Neolithic sites along the Yellow River valley. What they discovered were remarkably well-preserved starch grains that tell a story of early agricultural experimentation and dietary adaptation.

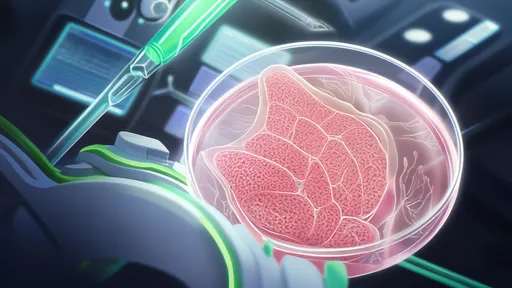

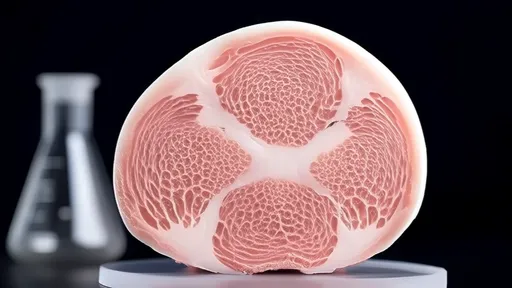

Starch grains don't lie. These microscopic time capsules retain their structural characteristics for millennia when protected from moisture and microbial activity. The team identified starch from multiple plant sources, including millet, Job's tears (a type of Asian barley), and surprisingly, from tubers that may represent early attempts at domesticating wild root vegetables.

The particular combination and condition of these starch grains suggest they underwent a cooking process consistent with porridge-making. Some grains showed signs of gelatinization - the swelling and bursting that occurs when starch is heated in water. Others displayed partial gelatinization patterns indicating intermittent heating, possibly from being simmered over a low fire for extended periods.

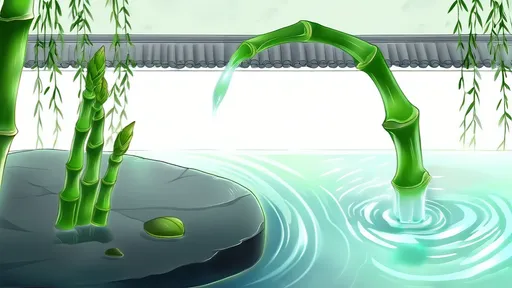

What makes this discovery particularly significant is the vessel in which these residues were found. The Tao Li pottery, with its unique three-legged design, represents one of humanity's earliest specialized cooking technologies. Its wide belly and narrow mouth would have been ideal for slow cooking grains in liquid, while the tripod base allowed for stable positioning over a fire. This artifact essentially serves as the Neolithic equivalent of a modern-day slow cooker.

The research challenges previous assumptions about Neolithic diets in East Asia. While millet cultivation was known to be widespread during this period (approximately 7000-5000 BCE), the presence of multiple grain types in single vessels suggests more complex food preparation than simple gruel made from a single grain. The inclusion of tuber starches hints at flavor combinations and nutritional considerations that go beyond basic subsistence.

Dr. Liang's team went beyond mere identification of the starch sources. By comparing the archaeological samples with modern equivalents subjected to various cooking methods, they reconstructed probable preparation techniques. The evidence points to a multi-stage process where different ingredients were added at intervals to achieve optimal texture. Some grains showed less damage, suggesting they were added later in the cooking process, while others were thoroughly gelatinized, indicating prolonged heating.

The social implications of this discovery are profound. Porridge, as opposed to plain boiled grains, represents a culinary innovation that requires planning, patience, and presumably, shared eating practices. The ability to combine multiple ingredients into a single dish suggests the development of recipe-like knowledge transmission within these early agricultural communities.

Furthermore, the presence of starch residues in multiple vessels across different excavation sites indicates that this was not an isolated practice but rather a widespread culinary tradition. The consistency in starch combinations across regions hints at established dietary preferences and possibly even early forms of regional cuisine differentiation.

This research also provides new insights into the nutritional status of Neolithic populations. The combination of cereals and tubers would have provided a more balanced array of nutrients than either food source alone, potentially contributing to population health and growth during this crucial period of human settlement and agricultural development.

As with any groundbreaking discovery, this study raises as many questions as it answers. Future research directions might explore whether these early porridges included other ingredients like meats, nuts, or seasonings that wouldn't leave starch evidence. The team also hopes to analyze lipid residues from the same pottery to complete the picture of Neolithic cookery.

The humble porridge, often considered the most basic of foods, emerges from this research as a significant milestone in human cultural development. These findings remind us that the transition from hunter-gatherer to agricultural societies involved not just new ways of producing food, but new ways of thinking about, preparing, and sharing it. The Tao Li vessels and their starch grain contents stand as silent witnesses to one of humanity's oldest surviving culinary traditions.

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025