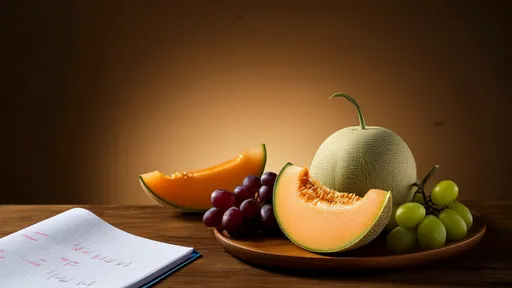

The vast, sun-drenched landscapes of Xinjiang have long been celebrated for producing some of the world’s most succulent fruits. From honey-sweet Hami melons to crisp, juice-laden grapes, the region’s agricultural output thrives under a unique climatic alchemy—intense sunlight paired with dramatic diurnal temperature shifts. This phenomenon, often overlooked in global discussions about terroir, is the secret behind Xinjiang’s unparalleled fruit quality. The science is as elegant as it is brutal: daylight hours bathe crops in photosynthetic energy, while nighttime cold snaps force plants to conserve resources, concentrating sugars into a symphony of flavor.

Nature’s Candy Factory

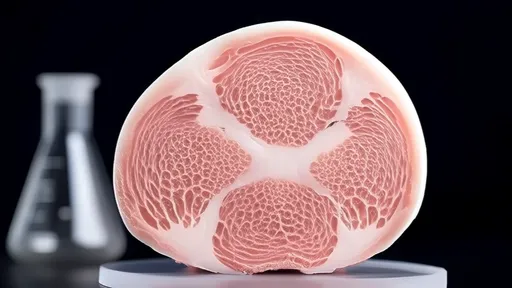

Xinjiang’s geography reads like a recipe for sugar synthesis. Nestled in China’s arid northwest, the region’s continental climate delivers over 2,800 hours of annual sunshine—more than California’s Central Valley. But it’s the 15-20°C (27-36°F) daily temperature swings during growing season that transform ordinary fruits into crystalline marvels. As dusk falls, plunging temperatures slow cellular respiration to a crawl. Sugars produced during daylight photosynthesis, which would typically be metabolized overnight in milder climates, become trapped within the fruit’s flesh. This daily freeze-thaw cycle of biochemical activity creates what agricultural scientists call "the compression effect"—a natural candy-making process perfected over millennia.

The Turpan Depression, a sunken basin lying 154m below sea level, exemplifies this phenomenon. Here, vineyards producing raisin grapes experience daytime highs of 45°C (113°F) and nighttime lows near 10°C (50°F). The resulting grapes achieve Brix levels (sugar content measurements) surpassing 24°, rivaling premium Napa Valley harvests. Local farmers speak of the cold desert nights "locking in" sweetness like nature’s refrigeration—a poetic truth with solid biochemical foundations. Phloem transport systems in the vines slow to a near halt after sunset, causing sucrose accumulation that daytime heat alone could never achieve.

Historical Roots of a Modern Advantage

Ancient Silk Road traders first documented Xinjiang’s "magic fruits" in 2nd century BCE texts, marveling at melons that tasted "as if soaked in honey." Modern research confirms these observations weren’t hyperbolic. A 2023 study published in Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry analyzed Hami melons grown under Xinjiang’s temperature fluctuations versus greenhouse-controlled conditions. The field-grown specimens contained 37% more reducing sugars and 22% higher antioxidant levels. This isn’t merely about sweetness—the stress-response compounds generated during cold nights create complex flavor profiles balancing sugar with acidity and aromatic volatiles.

Traditional Uyghur farming practices evolved to exploit this natural advantage. Farmers developed "dry farming" techniques, intentionally limiting irrigation to further stress plants. The slight water scarcity triggers survival mechanisms where plants funnel more resources into fruit development. Combined with the temperature swings, this creates what agronomists term "beneficial stress"—a controlled hardship that elevates crop quality. In Kashgar’s apricot orchards, this dual stress results in fruits with 19% higher dry matter content than those grown with ample water in temperate zones.

From Orchard to Global Market

Contemporary food scientists are decoding how to replicate Xinjiang’s conditions elsewhere—with limited success. Vertical farms in Japan have attempted to simulate the diurnal shift using LED lighting and climate control, but the energy costs prove prohibitive for commercial production. Meanwhile, Xinjiang’s melon exports grew 14% year-over-year in 2023, with premium varieties fetching prices comparable to Japanese Yubari kings in Asian markets. The region now accounts for 68% of China’s raisin production, with its flame raisins becoming staples in European bakeries and breakfast tables.

Climate change presents both challenges and curious opportunities. While rising temperatures threaten many agricultural zones, Xinjiang’s diurnal variation has actually increased by 1.3°C since 2000—potentially enhancing sugar compression effects. Some vineyards report harvests reaching unprecedented Brix levels, though vintners caution that excessive sugar can unbalance wine fermentation. The region’s agricultural colleges now race to develop new cultivars optimized for these shifting patterns, blending traditional knowledge with genomic selection.

As consumers globally develop more sophisticated palates, Xinjiang’s fruits stand poised to transition from regional specialties to internationally recognized luxury commodities. The very conditions that once made this remote region inhospitable—searing days, frigid nights, and relentless sunshine—have become its greatest agricultural asset. In an era where flavor is increasingly sacrificed for yield and shelf life, these fruits remain stubbornly, deliciously defiant—a testament to what happens when nature’s extremes conspire to create sweetness.

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025